TALLabs Bookshelf

Many freely-available works are well worth reading. Here is an assortment you may find valuable.Math

Calculus Made Easy

Calculus Made Easy by Silvanus P. Thompson, 1914. You can also read it online at www.calculusmadeeasy.org. An outstanding introduction to calculus, better than any standard textbook I've read. Let me reproduce the entire Chapter 1:No 1. To Deliver You From The Prelimiary Terrors

The preliminary terror, which chokes off most fifth-form boys from even attempting to learn how to calculate, can be abolished once for all by simply stating what is the meaning - in common-sense terms - of the two principal symbols that are used in calculating.

These dreadful symbols are:

(1) d which merely means "a little bit of."

Thus dx means a little bit of x; or du means a little bit of u. Ordinary mathematicians think it more polite to say "an element of," instead of "a little bit of." Just as you please. But you will find that these little bits (or elements) may be considered to be indefinitely small.

(2) ∫ which is merely a long S, and may be called (if you like) "the sum of"

Thus ∫ dx means the sum of all the little bits of x; or ∫ dt means the sum of all the little bits of t. Ordinary mathematicians call this symbol "the integral of." Now any fool can see that if x is considered as made up of a lot of little bits, each of which is called dx, if you add them all up together you get the sum of all the dx's, (which is the same thing as the whole of x). The word "integral" simply means "the whole." If you think of the duration of time for one hour, you may (if you like) think of it as cut up into 3600 little bits called seconds. The whole of the 3600 little bits added up together make one hour.

When you see an expression that begins with this terrifying symbol, you will henceforth know that it is put there merely to give you instructions that you are now to perform the operation (if you can) of totalling up all the little bits that are indicated by the symbols that follow.

That's all.

Flatland

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott (writing as "A Square"), 1884. A short novella about a two-dimensional being who is taken on a tour of one-dimensional Lineland, zero-dimensional Pointland, and three-dimensional Spaceland by a three-dimensional being. By reading it, you may begin to get a taste of how our own perspectives are limited, how our brains cannot fully comprehend things that are beyond our experiences and our senses.Science, Physics, etc.

Experimental Science

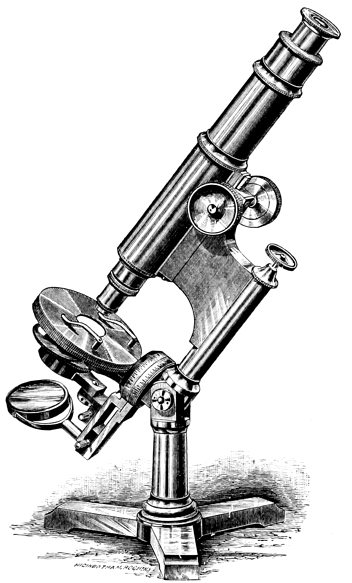

Experimental Science by George M. Hopkins, Copyright 1889 by Munn & CO. A large collection of science and engineering experiments and demonstrations. Many are "classics" that most science teachers already know about; many others are forgotten gems, well worth updating using what's readily available in our times.

Two New Sciences

Dialogue Concerning Two New Sciences by Galileo Galilei, translated into English by Henry Crew and Alfonso de Salvio, Copyright 1914 by Macmillan.A masterful set of dialogues among the fictional Simplicio, Sagredo, and Salviati, discussing the strength of materials and the science of motion. Wonderfully clear explanations of each of these topics, revealing a clear appreciation for experiment. Written and published during his house arrest resulting from the publication of his earlier Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

It strikes me that this, the greatest and most significant of Galileo's works, might never have been presented so clearly and carefully if not for his house arrest.

Read it to learn how to discover and explain scientific truths.

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

The Feynman Lectures on Physics by Feynman, Leighton, and Sands, Copyright 1963-1965, 2006, 2013 by the California Institute of Technology, Michael A. Gottlieb and Rudlof Pfeiffer.These lectures are "free to read, look at and listen to online" but not download or apply in other ways.

An excellent introduction to the field of physics, presented as a series of lectures to freshman and sophomore classes at Caltech in the early 1960's.

Teaching and Learning

How To Study

How to study by George Fillmore Swain, 1917. This short book is the inspiration for my own "How To Study" page; it's well worth reading all of it.General

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Originally published in English in 1793; this link is to The Harvard Classics edition from 1909, at Project Gutenberg.Bejamin Franklin lived a remarkable life, in a remarkable time. His experiences are well worth learning about, for people with almost any interests - creative writing, publishing, science, politics, abolition, humor, invention, and general playfulness. And his pleasant way with language continues to shine through, all these years later.

The Autobiography covers an earlier portion of his life, and stops short of those things for which he is (his participation in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution) or should be (his work, at the expense of his reputation, toward abolishing slavery) best known.

Harvard University President Charles W. Eliot chose The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin as the first section of the first volume of The Harvard Classics: Dr. Eliot's Five-Foot Shelf of Books. The entire set (originally published 1909-1910) is well worth your time. You can find them at The Internet Archive and myharvardclassics.com